Courageous Unstoppable You: Facing Yourself to Find Happiness

- Home

- Blog

“You are not a side effect of your life, you are an active participant in your own well-being.”

– P.T., a 40 year old woman, reflecting on what it means to face herself in psychotherapy

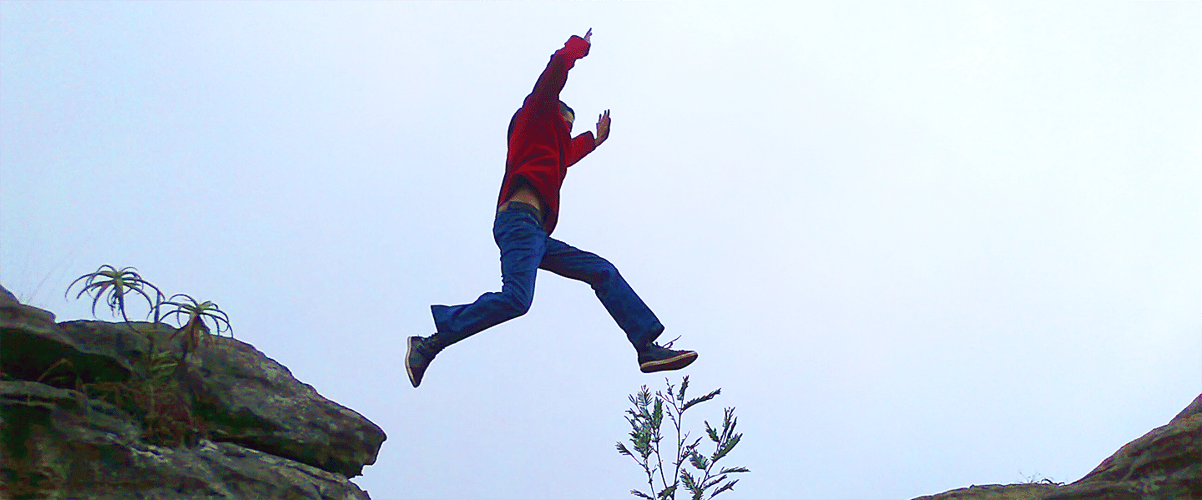

By the time this blog hits your inbox, we’ll be halfway into the first month of the New Year. This, dear reader, is a time of resolutions. We’re resolved to get our bodies into top shape, or to commit to healthier habits. We’re determined to be better in our relationships with family, children, or other loved ones. We’ve made up our minds to procrastinate less, be more efficient, more productive, wake up on time, go to bed early… the list goes on and on. These end-goals are admirable in their own right—but what is a resolution at its core? To me, it’s the conscious determination to actively take charge of your own life. So to all the cynics out there, I want to first and foremost encourage you to push onward: Because when we decide to take responsibility to change what dissatisfies us about our current selves, we are pursuing a fundamental human need to grow and develop as a person. In that simple phrase—Take charge of your own life—there lies a valiant message of hope, courage, and determination. There is bravery in taking control of your destiny, your fate. And this week—this year—I want to encourage you to pursue one resolution to its fullest: Reader, I want to help you take charge of your mental health. And the first step on that journey is to consider whether taking on a partner in that journey. A smart, caring, empathetic therapist might just be the missing piece of the puzzle that is you.

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.” This quote from Aristotle is the cornerstone of all insight-oriented psychotherapies. I genuinely admire those who engage in psychotherapy and commit to seeing it through – thereby bringing about personal emotional growth and a more satisfying life. Patients enter therapy for a variety of reasons. Perhaps they want to end a pattern of self-sabotaging behavior; where they may deny themselves the experience of true intimacy with another, behave in ways that preclude the possibility of joyful living, repeatedly choose narcissistic personalities with whom they fall in love, or find other ways to unconsciously live out what is known as “the repetition compulsion.” There may also be recurring symptoms of anxiety or depression for which they seek understanding and symptom relief. A life crisis around the end of a love relationship, the illness or death of a loved one, or severe job stress may lead one to seek therapy on an urgent basis, seeking immediate relief.

What is necessary in making this commitment to therapy, in sitting with a psychotherapist and examining one’s life? At its core, the psychotherapeutic relationship requires shared courage on the part of the patient and the therapist. At the beginning of psychotherapy, and from time-to-time throughout its course, the experience can feel quite scary for the patient. Coming to terms with certain realities heretofore avoided is emotionally challenging, and may feel daunting and overwhelming. At times extremely painful feelings, embarrassing or shameful fantasies, and troubling memories will arise during the course of therapy, all demanding the courage to confront, explore, understand, and resolve them.

Then there is the phenomenon known as “resistance” that develops during the course of psychotherapy. Resistance is based in defense mechanisms that protect the conscious mind from experiencing emotionally threatening unconscious memories, fantasies and feelings. Sometimes resistance is experienced as an urge to run – to avoid facing these issues – as it is human nature to seek pleasure and avoid pain. Internal conflicts also arise over feelings of dependency toward the therapist, in opposition to feelings of wanting to remain independent and self-sufficient. This is often manifested by the belief that seeking treatment is “a sign of weakness” and that “I should be able to manage my problems without the help of a therapist.” To the contrary, when one commits to the therapeutic process and sees it through to conclusion, it is a sign of admirable strength of character.

Two novel perspectives on therapy were recently shared with me. A young patient of mine – a tough, charismatic, and highly talented college football player – put it like this, “You have to man up, and face yourself in therapy.” Another patient, a middle-aged professional woman from the financial services industry, described therapy as a place where “You are not a side effect of your life, you are an active participant in your own well-being.”

Patients will commonly develop unconscious and conscious feelings and fantasies toward the therapist, called “transference,” that must be openly discussed in the session, no matter how embarrassing it might feel. The patient “transfers” onto the therapist feelings and fantasies they had toward important figures from their earlier life, such as their parents. These may include longings to be loved, fearfulness, erotic fantasies, yearnings to be taken care of, and so on. If the transference feelings are not candidly revealed, the therapy will grind to a halt. An open and honest discussion will pave the way toward uncovering important unresolved issues with one’s mother or father that, once resolved, enable one to move on with his or her life and love relationships in a healthier fashion.

The therapist in turn will develop a “countertransference” toward the patient. Countertransference occurs when the patient elicits conscious or unconscious feelings, fantasies and memories in the therapist based upon how the therapist was raised by his or her parents, and from other important relationships. It is important that the therapist have engaged in his or her own personal psychotherapy or psychoanalysis, to be able to identify and analyze their countertransference reactions (particularly the unconscious ones), so as to not act them out on the patient, or contaminate the therapy through imposing their own personal neurotic agenda. Among the most challenging and beneficial experiences in my own life were the years I spent on the psychoanalysts’ couches – first as a psychoanalytic institute trainee – and later following the death of my father – both of which helped to forge my identity as a psychiatrist. A personal psychoanalysis enables the psychiatrist or psychotherapist to more effectively empathize with, support, and emotionally “hold” their patient while being mindful of the potential interference from one’s own childhood relationships.

An important element in longer-term psychoanalytic or psychodynamic therapy is analyzing the unconscious causes of self-sabotaging behaviors that often originate in childhood relationships. In the course of therapy, as the patient grows increasingly familiar with the technique of “free association”, he or she will speak whatever comes into their mind, without holding back or censoring their thoughts, fantasies or feelings. As free association proceeds, the patient may re-experience prior events in his or her life with great emotional force, at times so powerful that they literally believe that they are actually living through the experience at that moment. This is called abreaction. As a result of the abreactive experiences, and the caring and empathy provided by the therapist, the traumatic event may be recast in a new cognitive framework, and be viewed without distortion through adult eyes, enabling the patient to finally let go of the trauma and leave it behind.

The foundational elements of a successful therapy include tenacity, the development of trust, feeling understood and cared about, feeling emotionally “held” through difficult and painful moments, mutual respect, a high level of technical skill on the part of the therapist, and a shared optimism regarding the outcome. The therapist must also embody a deeply held belief in the human spirit’s capacity for growth and change. Ultimately it takes heart, and a strong belief in the patient’s (and one’s own) courage, to forge ahead into the unknown.

Related Information

- Learn about Genetic Testing

- Learn about Potomac Psychiatry

- Meet Our Doctors

- Contact Potomac Psychiatry